Early Life

Alfred Huberman was born Abram Huberman on 20 December 1927 in Pulawy in Poland. He was the only son of Moshe and Czarna and had five sisters.

The photograph below is the only surviving photograph of Alfred with his sisters. His sister Rivka has her arm around Alfred; the two older sisters were called Franya and Ides and the youngest child Perla is sitting next to Rivka’s twin, Tzril.

© Huberman Family

Alfred had a happy childhood; it was a very caring family and they all got on well together. His father was a shoemaker and although they weren’t very well off, they were well looked after and his mother always made sure they had plenty of food and were well dressed. Alfred’s father Moshe was always helpful to others in need.

© Huberman Family

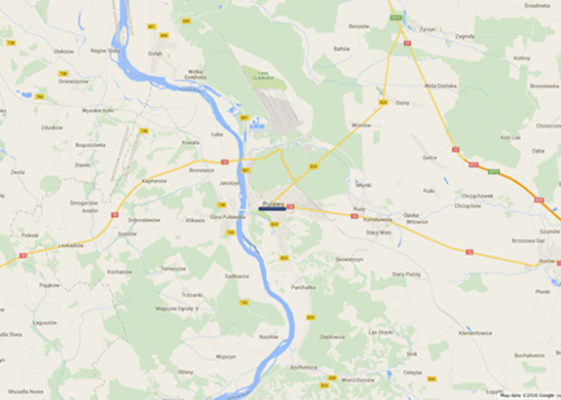

Alfred often used to visit his grandparents in their house on the sand by the river Vistula in Pulawy. When he was seven he took and passed an entrance exam for school and later he remembered the schoolchildren having to wear a black armband when the Chief of State, Józef Klemsn Pilsudski died in 1935.

He enjoyed school and was very bright, a natural linguist and excelled at writing and composition. He used to write and compose many letters for people in the town who had relatives in Palestine and France and elsewhere. When Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, the Headmaster Hendryk Adler, asked the class to write letters to a Czech school welcoming them to Poland. Alfred’s was chosen since it was the best letter with the neatest handwriting.

Alfred attended school with a cousin who used to defend him when they began to encounter anti-semitism. In September 1939 Pulawy was seized by the Nazi-Germany armed forces; Alfred’s house was demolished and the family were forced to find alternative accommodation.

© Google 2016

1939 – Early 1944

When their house was demolished, Alfred and his family went to live with his grandparents. Although there were only two rooms it was in a part of the ghetto that the Jewish population of 3,600 were forced to live in by the Nazi-German soldiers.

On a frosty night on 29 December 1939 the family were told to leave and move on. They managed to find accommodation in a village called Parchatka. Initially conditions weren’t too hard as the village was in a farming area and food was readily available. Whilst living there one of his twin sisters, Rivka, who had been staying with relatives in Warsaw, died in hospital after their house was destroyed in an air raid.

Alfred and the rest of his family were able to stay in the village for two years before again being evicted. But in 1942 they had to cross the river Vistula although they ignored advice to move to another town and instead were forced to live in two other ghettos, Parchatka and one at Zwolen. This ghetto was established in the southern part of the town where thousands of Jewish families from the town itself and from neighbouring villages were concentrated.

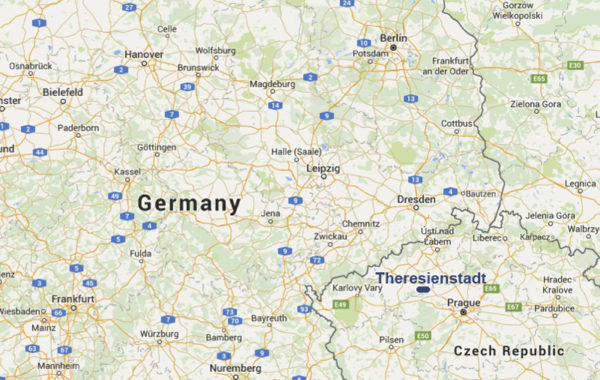

Map data 2016 © Google (added graphics)

Alfred only stayed there for four days. Families were rounded up by soldiers in tanks and sent to the market place; if any refused to leave, the dogs were sent in or they were shot. Selection then took place and the families were segregated into groups of men and women and ages. Alfred was separated from his father and this was the last time he saw either him or the other members of his family.

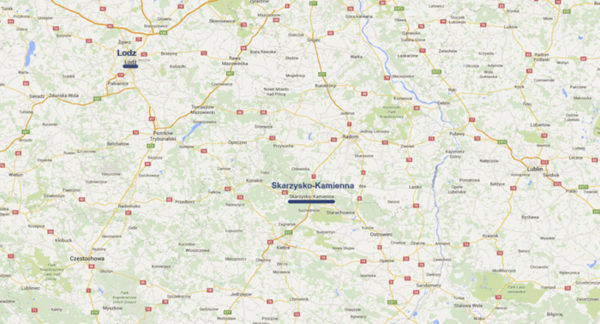

A group of young men, including Alfred, and women were selected in Zwolen and sent by lorry to a slave labour camp in Skarzysko-Kamienna. During the journey Alfred witnessed the murder of one of the young men. Although he had bribed a German soldier with money, he was shot whilst trying to escape. On arrival Alfred was assigned to C camp, initially working in transport unloading scrap metal, iron ore and slack, a bi-product of metal.

Later he worked in a room where women melted TNT from powder into liquid that was poured into copper buckets and then into shells. When the liquid solidified Alfred’s job was to bore holes in the shells, ready for the detonators to go in. There were twelve-hour shifts either working all day or all night, and the toxicity levels were such that the workers became yellow.

There was only ersatz coffee (substitute for coffee) for breakfast, and soup at lunch time; the life expectancy on this ration was only 3–4 months but fortunately Alfred was helped by a Polish worker who came from the town who gave him some food, and later, he was given scrapings of milk from the bottom of the churns in the camp by another worker. Only because of this was he able to last at the camp for 18 months but later he described it as one of the worst camps he was in.

At the beginning of 1944 Alfred was moved to another camp at Czestochowa in southern Poland.

1944 – 1945

In early 1944, and as the Russian army advanced, Alfred was sent to Czestochowa labour camp.

The Jewish workers were completely dispensable to the Nazi-Germans; frequent selections were made and those unsuitable for work were either shot or transported to extermination camps. Others died of hard labour or starvation. They were unable to get much sleep since the sleeping conditions – as in many camps – were terrible. The mattresses were made of straw and the over crowded 3-tier bunks very fragile. There was constant bombardment during the night. Alfred was amused though to see that the Germans too were frightened.

Alfred worked again in the transport section. His trousers had started to fall apart and he was sent to get them repaired. To his amazement he found his second cousin, Jacob Weinstock working there and sewing on a machine. He had also lived in Pulawy and was able to give Alfred some extra food.

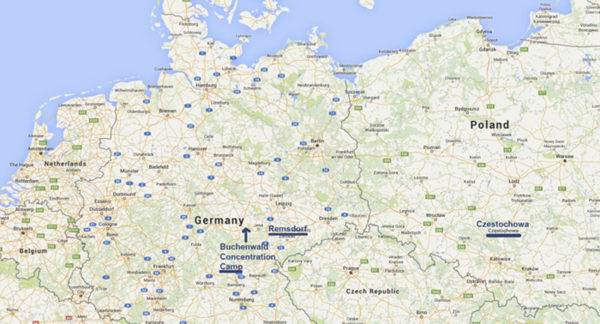

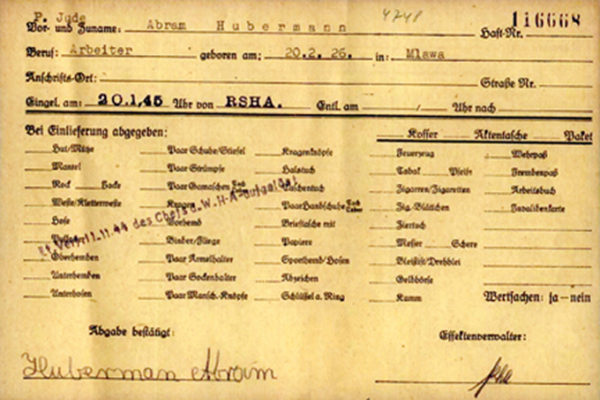

Alfred and his cousin were sent to Buchenwald concentration camp in late 1944; the journey by cattle train trucks took days, shunting to and from, day and night and they only received a bread ration for a day or two. As soon as they stepped off the train, huge German shepherd dogs were waiting for them. They were led to a walled-in enclosure with a tank full of strong disinfectant, stripped and all possessions taken including the only photographs Alfred still had. The soldiers used long poles to make sure they were fully submerged. After the ‘bath’ they were issued with striped jackets and shoes and taken to Barrack No.52. His number was 116668.

Fortunately Alfred was only in Buchenwald for three or four weeks. He volunteered to fetch the soup to make sure he could have an extra ration. The toilets (for approximately 1,000 prisoners) consisted of a ditch with a tree trunk across; those who were weak or disorientated sometimes fell in. They had to endure frequent counts, and since there were approximately 40,000 prisoners, they were forced to stand in freezing weather conditions for many hours.

In early 1945 Alfred was transferred to Remsdorf camp (Troeglitz), a Buchenwald subcamp. He arrived by train at night and had to sleep in the open in melting snow.

The following morning he awoke to find an outline of his body in the snow. The prisoners were lined up to go to work filling in holes in the fields caused by the bombardments. Although in the fields Alfred could sometimes find bits of carrots or potatoes to eat, the conditions were tortuous. He was forced to always carry something heavy back to the camp – either bricks, the disabled or dead bodies.

By this time Alfred had started coughing up blood but he was determined to try and live until the end of the war but he was again transferred. He travelled by train in an open truck that was full of dying prisoners, some of whom died of dysentery after eating leaves at occasional stops on the journey.

The advancing American army shelled the trucks and those who were able jumped off and escaped. Alfred discovered an empty hotel where he found a large amount of food that he hid in a suitcase, shoved loaves under his arm and a sausage under his jacket. Sadly, everything was grabbed from him by others, but he did have one bite of sausage, before he was rounded up by the Hitler youth and sent on a ‘Death March’, marching through villages and towns for three weeks. Since he had lived in a country village he was at least able to identify plants and herbs that he could eat. 2000 prisoners left Remsdorf and only about 800 were still alive when they arrived at Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia.

The Jewish inmates were shocked at the state they were in. They were allocated places in the military barracks, but since they had no idea how long the war would last, the rations were halved. However, on May 8th 1945 the Russian Army liberated the camp.

Liberation and arrival in Windermere

At Theresienstadt, Alfred sat on some of the Russian tanks and met the soldiers who had arrived to liberate the camp. He walked outside to see what it felt like to “be free” and in a nearby field found a dead soldier’s belt; on it was etched the words ‘God is with us’.

By this time Alfred had a high temperature, and didn’t feel very hungry. Fortunately he didn’t go to get extra food rations since some of those who did had dysentery and died. Alfred was accommodated in the German soldier’s barracks, received medical attention and allowed to have showers for the first time in many years.

A Czech doctor at Theresienstadt contacted a Jewish charity that negotiated with the authorities to bring a group of child Holocaust Survivors to England. Very few of the children wanted to return to Poland; some of those who did return initially couldn’t find their families and were threatened with murder.

In June 1945 the Home Office gave permission for a thousand orphans aged from eight to sixteen to be brought to the UK for recuperation, and ultimate re-emigration overseas. The Home Office were made aware that it was unlikely that any documents would be available giving proof of age, and the children rescued from concentration camps would most probably have no identification papers of any kind.

With this fact established, the first three hundred children were moved from Theresienstadt to Prague. Alfred was one of those chosen to make the journey and later remembered his short stay in Prague, meeting very kind and friendly Czechs and being taken to a circus before his flight with the other children.

On 13 August 1945, ten Stirling aircraft of 196 Squadron set off for Prague from the UK to collect the children and other passengers, in order to transport them to the Lake District. According to immigration officials the first of the Stirling aircraft to arrive at Crosby on Eden from Prague touched down at 5.00pm on 14 August 1945.

A series of buses was used to transport the children to Windermere, though towards the end army trucks had to be co-opted and the final passengers departed from the airfield at 10.30pm.

Alfred’s first new home in England was on the now ‘lost’ village of Calgarth Estate that stood at Troutbeck Bridge, about one mile from Windermere. Calgarth Estate was a wartime housing scheme built for aircraft factory workers employed at nearby White Cross Bay. The estate had its own shops, canteen, entertainment hall and many other facilities.

On his arrival Alfred’s only possessions were some shorts and a ladies’ jacket. The children were given clothes, their own small room, a bed and clean linen.

By this stage Alfred’s illness had been diagnosed as tuberculosis. He was only at Windermere for a few days before he was taken to the Westmorland General Hospital. He was then transferred to the TB Colony at Papworth where he shared a room with an RAF airman called Bill Shepherd. With his expertise in learning languages, Alfred quickly learnt English so he could speak to Bill.

From Papworth Alfred was sent to stay in the Bolney Block at Ashford Sanatorium where he met up again with Minia Jay, one of the few girls who had come with him to Windermere. Coincidentally, years later, the site at Ashford became a training school for the police and Alfred’s son trained as a policeman there.

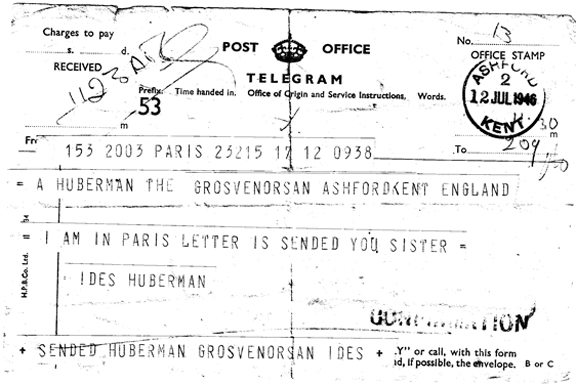

After his discharge at Ashford, Alfred returned briefly to Windermere. Whilst he was there he discovered, to his great delight, that one of his five sisters, Ides had survived the war. One of ‘the boys’, Sam Dresner, was reading a Jewish newspaper where people, who were trying to find out if their relatives were still alive, wrote making enquiries. Alfred decided to write to the paper and gave names of his family members. An aunt living in France, who was still alive and in contact with his sister Ides who was also living there, rushed to see her and told her ‘she had won the lottery’. During an English lesson while he was staying at Ashford, Alfred received a telegram sent on the 12th July, 1946.

Alfred was to be reunited with Ides later that year.

Life in Southern England

Whilst at Windermere his sister sent him the address of a distant relative (Sophie) who lived in Hove. She and her husband, Lou, traveled to Windermere to meet Alfred and following further visits, asked him to stay with them in Hove. There he met Sophie’s father who owned some tailoring shops. Alfred wanted to get back to be with ‘The Boys’ but knew they would eventually be dispersing and so he decided to move permanently to Hove and begin a new life. Asked if he would be interested in learning how to be a tailor, he agreed and so became apprenticed to the tailoring business.

He decided that he needed to get involved with people in the area and joined sports and youth groups where he played tennis and table tennis and soon made many friends. He also went to evening classes and learnt French and further tailoring and other clothes making skills. He stayed in touch with ‘The Boys’ and many of them visited and were welcomed by Sophie and Lou.

He cycled and frequently went out with friends. He became a member of the youth club table tennis team who played in the local league and won many trophies. His defensive skill was much admired, particularly when his opponent in tennis and table tennis was considerably larger in size.

At the Youth Group he met Shirley, who had recently moved from London. They got married on the 18th December 1955. Alfred’s best man was Mendel Preter, also one of the child Holocaust Survivors who had stayed in Windermere in 1945 and who had been in the Westmorland General Hospital at the same time. Alfred and Shirley had three children Caroline, Maurice and Bryan.

Alfred continued tailoring with Sophie and Lou and then went for an interview with BT and was delighted to be accepted for training as a telephonist (a huge achievement as he had only known the English language since arriving in Windermere). To augment his income he tailored by day and worked at the local Telephone exchange in the evenings and weekends.

Alfred had at this time become a very experienced ladies’ tailor and decided to also learn tailoring for men. Since there was by now nothing beyond his tailoring knowledge, he was approached by the Brighton Department store and offered a suite of rooms in which to set up his business. He quickly became established and was known for his skill in making problem clothing fit perfectly. With his friendly personality the workroom became a place people enjoyed visiting.

Alfred and Shirley continued to see Ides until she died aged 53 and the family still retain close contact with her two daughters, six grand nieces and eight great-grandnieces and nephews who still live in France.

Hanningtons the Department store closed in June 2001 and Alfred continued working as a tailor from home. His workshop is still as it was in 2011.

Short excerpt from ‘Alfred’s Workshop‘ film © Huberman Family

Alfred gave many talks to both children and adults about his experiences during the war. He used to say how important it was to communicate these and to try and ensure similar events never would recur…. “if I don’t speak, who will?”.Alfred died in 2011 but he left a valuable legacy – six grandchildren and one great grandchild. Shirley and their children have carried on ensuring that his experiences during the war and those of others will not be forgotten.

© Huberman Family